This is one of a two-part blog discussing scars. This first part discusses scar types and the second part will discuss scar therapies. There seems to be a lot of confusion amongst the general public regarding scars, why and when they occur, and how they are treated. When I first started private practice, 12 years ago, I took emergency room call on a regular basis. I would get called at all hours of the day and night to repair lacerations, dog bites, and many other major soft tissue and bony injuries. I would get this call from the emergency room on a regular basis: “Dr. Brown, a patient is requesting you to come to the emergency room to sew up their laceration so that they will not have a scar.” Similarly, during cosmetic consultations with prospective patients, I am bewildered when a patient is surprised to learn that a scar will result from surgical intervention. With this blog, I hope to clarify some common misconceptions about scars and scar treatments.

Scars

Scars are the result of surgical intervention or injury. There is no way around it. Scars will result from surgery and scars are permanent. There is no such thing as “scar-less surgery”. Stretch marks are considered scars and are permanent. When scars are fresh, they are red, and over time they fade to a more natural skin color. Scar maturation refers to the time it takes for a scar to fade and soften to reach its’ final quality after going through all the stages of wound healing and collagen remodeling. Collagen remodeling involves a balance between formation and destruction, which occurs during normal wound healing. In most individuals this process takes 12-18 months, but could take longer. The bottom line is that scar appearance improves with time. All individuals heal differently and form a unique type of scar consistent with their inherent healing ability. Some individuals form scars that are of excellent quality, meaning they are barely seen. Others form more visible scars.

Plastic surgeons are specialists at skin and soft tissue closure, understanding anatomy, skin tension, and tissue movement like no other. We are experts in hiding scars in natural creases and shadows of anatomic lines, while minimizing tension forces on healing incisions. We obtain inconspicuous scars by meticulous repair, minimizing scar lengths wherever possible. I always prefer least invasive modalities for intervention while optimizing contours and appearance.

There seems to be a great deal of confusion about keloid scars. I will always ask prospective patients if they have a history of poor scars or keloids. When a patient tells me they have a keloid scar, the majority of the time, it is not a true keloid.

Keloid Scars are scars that enlarge and spread beyond the borders of the initial wound. They outgrow the site of the injury or scar similar to a tumor, but they are benign. They are more common in African-American, Asian, and darker skinned patients but can occur in patients of any race. They are most common on the central chest, shoulders, and earlobes. In my practice, true keloid formers are actually quite rare. I have only a handful of patients with keloid scars and we know each other quite well. No one really knows why keloids form, and there is no definitive treatment. Treatment is incredibly frustrating, as they often recur and do not tend to improve with time on their own.

Hypertrophic Scars are much more common. If a patient describes a history of poor scarring, this is usually the culprit. These are scars that become raised, ropey, and red, and often have localized symptoms such as tenderness and itching. They do not enlarge beyond the limits of the scar. They usually begin to develop about 4-6 weeks after surgery and can fluctuate over time, with exacerbations and improvements until the scar matures.

Pigmented Scars or dark scars are also occasionally seen. Basically, the scar becomes darker than surrounding skin as a result of inflammation, which stimulates melanocytes to secrete melanin, which tans the skin. I see this more frequently in darker skinned patients.

Hypopigmented Scars or white scars can be lighter than your surrounding skin. This occurs because the melanin producing cells can’t penetrate the scar.

Atrophic (depressed) or widened scars can occur because of tension, or thinned-out underlying tissues. Certain individuals may be prone to depressed or thinned out scars during collagen remodeling where collagen destruction slightly outweighs its formation.

Stay tuned to part two of this blog that will discuss scar treatments…

Dr. Hayley Brown MD, FACS

Las Vegas Plastic Surgeon

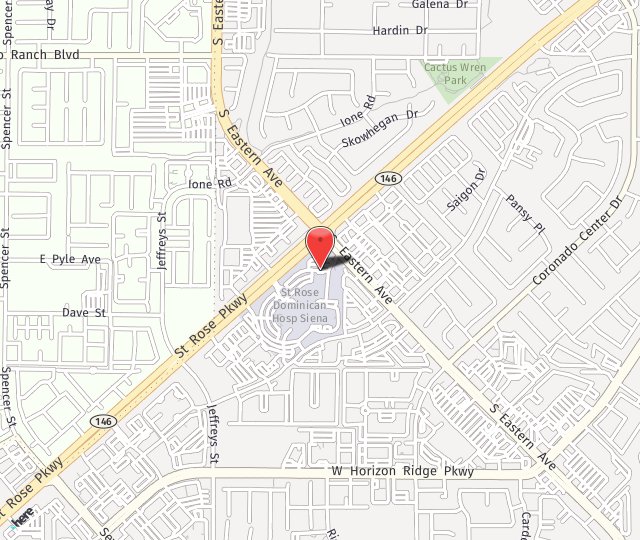

Desert Hills Plastic Surgery Center, Henderson and Las Vegas, Nevada